rückblick

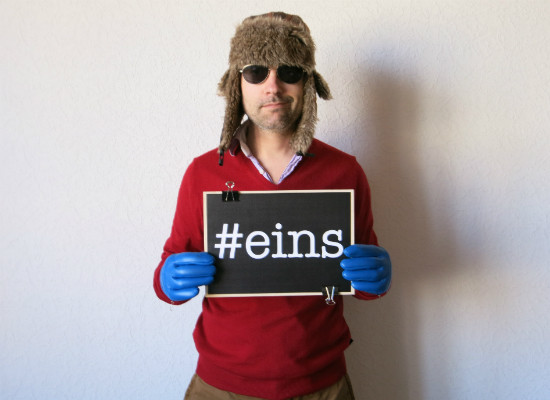

#eins. pianohero

06may14_21h

atelier der bildenden künste

digitale waren. frei im netz verfügbar. der künstler nur projiziert. auf der bühne sein alter ego. in fleisch und blut. mit herz und hirn. wer ist der pianohero?

er muss sich verhalten. zu seiner technischen umwelt. ohnmächtige unterwerfung? nutzung als katalysator der künstlerischen sprache? die technik an ihre spröden grenzen treiben?

privat oder öffentlich? das ist die frage. massenmedien. abgebildet im intimen atelierraum. öffentlich die individuelle reflexion des protagonisten.

programm

brigitta muntendorf: public privacy #2: piano cover

für keyboard, video und zuspielung

stefan prins: piano hero #1

für midikeyboard, live-elektronik und video

terry riley: keyboard study #1

für keyboard und video

dominic thibault: igaluk – to scare the moon with it’s own shadow

für keyboard und controllers

sergej maingardt: it’s britney, bitch

für keyboard, sampler und live-video

sebastian berweck lädt ein zu...

sebastian berweck über...

sebastian berweck, ein...

Was macht der Computer im Konzertsaal?

"Bei flüchtiger Betrachtung haben Musik und Strom nicht viel miteinander zu tun. Eine Sängerin singt, ein Geiger spielt mit Pferdehaaren auf Darmsaiten und ein Hornist bläst in einen meterlangen Metallschlauch – das alles sind wir gewohnt. Wenn aber ein Computer in einem Konzertsaal steht und damit Elekrizität ins Spiel kommt, weiß man nichts Rechtes damit anzufangen. Vielleicht fragt man sich sogar: Muss das wirklich sein? Müssen diese Büromaschinen jetzt auch noch hier herumstehen und mich mit ihrem Geblinke vom Geschehen auf der Bühne ablenken?

Doch die musikalische Verwendung von elektrisch betriebenen Geräten und ihre Virtualisierung im Computer ist heute aus den Konzertsälen nicht mehr wegzudenken. Es ist nicht immer auf den ersten Blick zu sehen, aber Computer sind zu einer alltäglichen Erscheinung bei Musikveranstaltungen geworden. Sie haben sich sogar zu veritablen Instrumenten gemausert."

aus:

Berweck, Sebastian: Was macht der Computer im Konzertsaal? Eine kurze Geschichte der Elektronik in der Musik, in: Kulturmanagement konkret 02/2008, S. 147–161)

On (re-)performing electroacoustic music

The best possible performance of a musical work could arguably be called a faultless performance, where according to Herbert Henck, a fault is defined as ‘any moment, where intention and doing fall apart’.(1) In a music performance, this does not only include manifest mistakes like wrong notes, but also ‘a slight inhibition and tenseness’,(2) since this condition and ‘the uncomfortable emotion that goes along with it stands squarely in the way of musical expression’.(3) A good music performance – and this then holds true for a performance of music with electronics, too – is therefore much more than just a technically faultless performance and requires meticulous preparation. However, if the preparation of a performance of an acoustic concert is compared with that of an electroacoustic concert, fundamental differences are revealed – even though the musical ends will be the same.

The pianist who wants to prepare a programme of Beethoven sonatas will be able to buy several editions of the score. Having obtained the music, a trained musician is then able to practise independently for the concert. Arriving at the concert hall, a building likely built for the purpose of playing classical music, a freshly tuned grand piano is waiting. The acoustics of the concert hall and the piano will now be tried out and the pianist will make adaptations to the interpretation, for example by reducing the tempo in very reverberant rooms. For the remainder of the day the pianist will concentrate on the performance and should feel well prepared when the concert begins. This routine caters to the needs of a pianist so that the best possible performance can be produced.

The performer of an electroacoustic concert is likely to have a thoroughly different experience. In searching for information on a certain composition, the instrumentation of the piece is not clear: can the piece for piano and live-electronics be played alone or is it a duo? Has it been written for a specific occasion and thus cannot be played in a regular concert hall? Is the synthesizer a stock synthesizer or a self-programmed computer patch?

Obtaining the score from a composer or a publisher, the performer might find that the electronics are not part of the score and that another institution has a financial interest in it. The piece might also require devices that are not part of the performer’s set-up and need to be bought or rented.

Furthermore, it is unlikely that the electronics immediately work on the performer’s computer because of the frequent changes in operating systems and programs. This requires updating the patches, which can be written in a large number of software languages used in the last three decades. The performer has to be knowledgeable in each of these languages or will again have to ask for help, which will probably bring yet another financial burden. Only then can the performer play the composition for the first time and decide if the piece suits the repertoire.

After the piece has become part of the repertoire the setting up of the concert hall, which is suited for acoustic music, poses more problems. The performer will have to bring all the electronics into the hall or will have to work with the technical team of the venue. Since a classically trained instrumentalist has likely not had any training on digital instruments and does not know how to convey technical information, the proposed set-up and the information might not suffice and the afternoon before the performance is a stressful set-up trying to get everything working for the concert. This setting up might commence right until the performance starts and a stressed performer will come on stage to play with an electronic instrument that has been constructed that very day and has not been tested. The evening performance has little chance to fulfil the above definition of a best possible performance; turning the weeks of preparation into a bitter experience the performer is likely to have no desire repeating.

As a performer of such music, I have encountered a number of solutions and opinions when discussing these experiences,

for example in private conversations but also at public events:(4)

- The breakdown of the electronics is comparable to piano strings breaking.

- Electroacoustic compositions are never solo pieces.

- Performers need to learn coding.

- The electronics are just like a musician who can make mistakes.

- Just like a violinist needs a luthier, a performer of electroacoustic music needs a technician.

- Emulation of old computer systems will soon solve any problems stemming from obsolete hard- and software.

From the performer’s view, these arguments are not very helpful for they do not relieve the performer of the above-described burdens. They also often do not hold up. If a piano string breaks, the pianist can simply transpose by an octave and finish playing the composition. The breaking of the electronics, however, will likely lead to the performance being aborted. The argument of the electronics making mistakes just as humans do does not hold up either: since mistakes in the electronics most likely result in a complete breakdown of the electronic part, faulty electronics should not be compared to a musician making a mistake but to a musician having to leave the stage during performance.

________________________________

1 ‘alle Momente, in denen Wollen und Tun auseinanderfallen’, Herbert Henck, Experimentelle Pianistik (Mainz: Schott, 1994), 105. Here and in every other occurrence foreign-language texts, except where noted, are translated by the author.

2 ‘nur [...] eine leichte Befangenheit und Verspannung’, Ibid.

3 ‘das ungute Gefühl, das ihn begleitet, steht dem musikalischen Ausdruck allemal im Wege’, Ibid.

4 For instance in the discussion following a lecture at the Ambiant Creativity – Digital Creativity and Contemporary Music conference at the ZKM Karlsruhe on March 17, 2011.

excerpt from:

Berweck, Sebastian (2012) It worked yesterday: On (re-)performing electroacoustic music. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield.

complete version available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/17540/